Ten years after the adoption of the Paris Agreement, climate adaptation has become a defining element of global climate policy. This shift did not begin in 2015, but Paris marked the moment when adaptation moved from a fragmented field of pilot projects and scattered vulnerability assessments to a recognised pillar of international climate governance.

Before Paris, adaptation efforts were growing but remained constrained: financing was limited, metrics were inconsistent, and national strategies were unevenly developed. The Paris Agreement, adopted on 12 December 2015, changed this trajectory by anchoring the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) and signalling that building resilience is integral to development pathways.

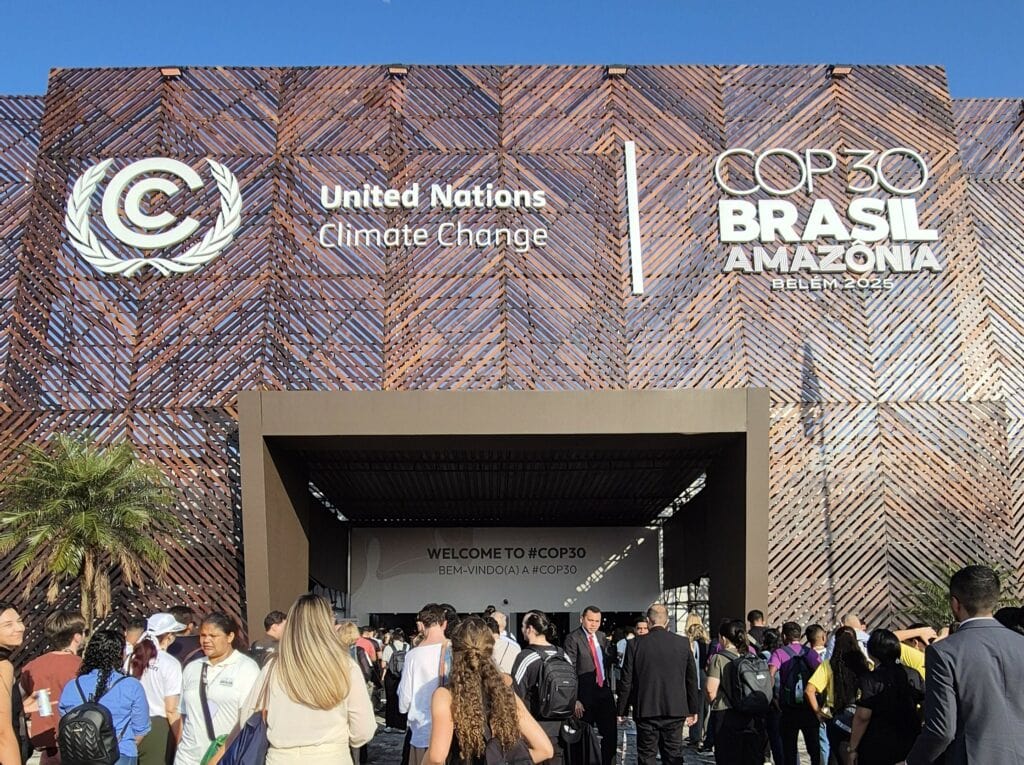

The decade that followed has fundamentally transformed the global adaptation landscape — in policy ambition, institutional infrastructure, financing, and international cooperation. These developments culminated at COP30, which marks the most advanced stage of adaptation governance to date.

Germanys Role

Germany, through the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), contributed steadily throughout this period. By supporting climate-resilient agriculture, social protection, disaster risk reduction, nature-based solutions, and national adaptation plans (NAPs), and by providing substantial funding to the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and Adaptation Fund (AF), Germany helped strengthen the adaptation architecture emerging since Paris.

A decade of Adaptation: Key developments since 2015

The evolution of adaptation since 2015 can be traced through the major negotiation cycles:

- 2015 to 2018 (COP21-COP24): Establishment of the fundamental architecture for international adaptation governance

With the GGA anchored in the Paris Agreement, countries intensified their national adaptation planning, e.g. in form of preparing their national adaptation plans (NAPs), while multilateral funds such as the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund expanded their adaptation portfolios.

- 2018-2019 (COP24-COP25): Adaptation receives additional support and became a recognised global development priority

Around COP24 in Katowice and COP25 in Madrid, new international initiatives emerged, most prominently the Global Commission on Adaptation, which reframed adaptation as essential for economic stability, human security and long-term development resilience. The debate also widened beyond technical measures to include social protection, ecosystem-based approaches and anticipatory risk management. By the time the negotiations reached COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, adaptation had become a central political concern, driven by increasingly visible climate impacts.

- 2021 (COP26, Glasgow): Intensifying expectation

Glasgow produced the political commitment to at least double adaptation finance from 2019 by 2025, signalling that international support needed to scale at a speed matching climate risks. The period from 2020 to 2022 witnessed both heightened ambition and growing frustration. While planning processes advanced and political attention increased, finance remained insufficient and local implementation often lacked predictable, long-term resources. Initial discussions on metrics and methodologies for the GGA also gained momentum, though consensus remained distant.

- 2022-2023 (COP27-COP28): Assessment of global progress

Negotiations — including COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh and COP28 in Dubai — increasingly focused on clarifying how global progress on adaptation should be assessed. Technical work under the GGA was structured and advanced through the identification of thematic areas and the initiation of work on potential indicators, methodological options and data requirements. Despite increased contributions from developed countries, available funding remained far below the levels needed in developing and particularly vulnerable countries. As discussions evolved, the need for a coherent and operational global framework became more evident, culminating in the adoption of the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience and the launch of a work programme to further develop adaptation indicators.

By 2024 and 2025, momentum built ahead of COP30. Negotiations increasingly aligned around the need for a consolidated global indicator framework, while at the same time exposing substantial gaps in methodologies, institutional capacities and data systems. The run-up to Belém was therefore marked by intensive technical coordination – a preparatory phase that ultimately led to the adoption of 59 global adaptation indicators at CMA7. Read more about COP30 and the state of global adaptation in our in-depth article.

Conclusion: Adaptation Has Matured – But the Hardest Work Lies Ahead

Ten years after Paris, adaptation policy has evolved from political signalling into structured governance. Indicators, plans, financing mechanisms and global initiatives now form an architecture that did not exist a decade ago. CMA7 represents the most comprehensive expression of this architecture so far.

Yet adaptation still lacks the resources, data and systemic implementation needed to match the scale of climate risks. The coming decade must address the challenges. National and local implementation, long-term financing and improved metrics will decide whether the ambitions embedded in the GGA can translate into resilient livelihoods, ecosystems and economies.

Adaptation is not peripheral. It is central prerequisite for sustainable development – and its importance will only continue to grow given the progressing climate change impacts.