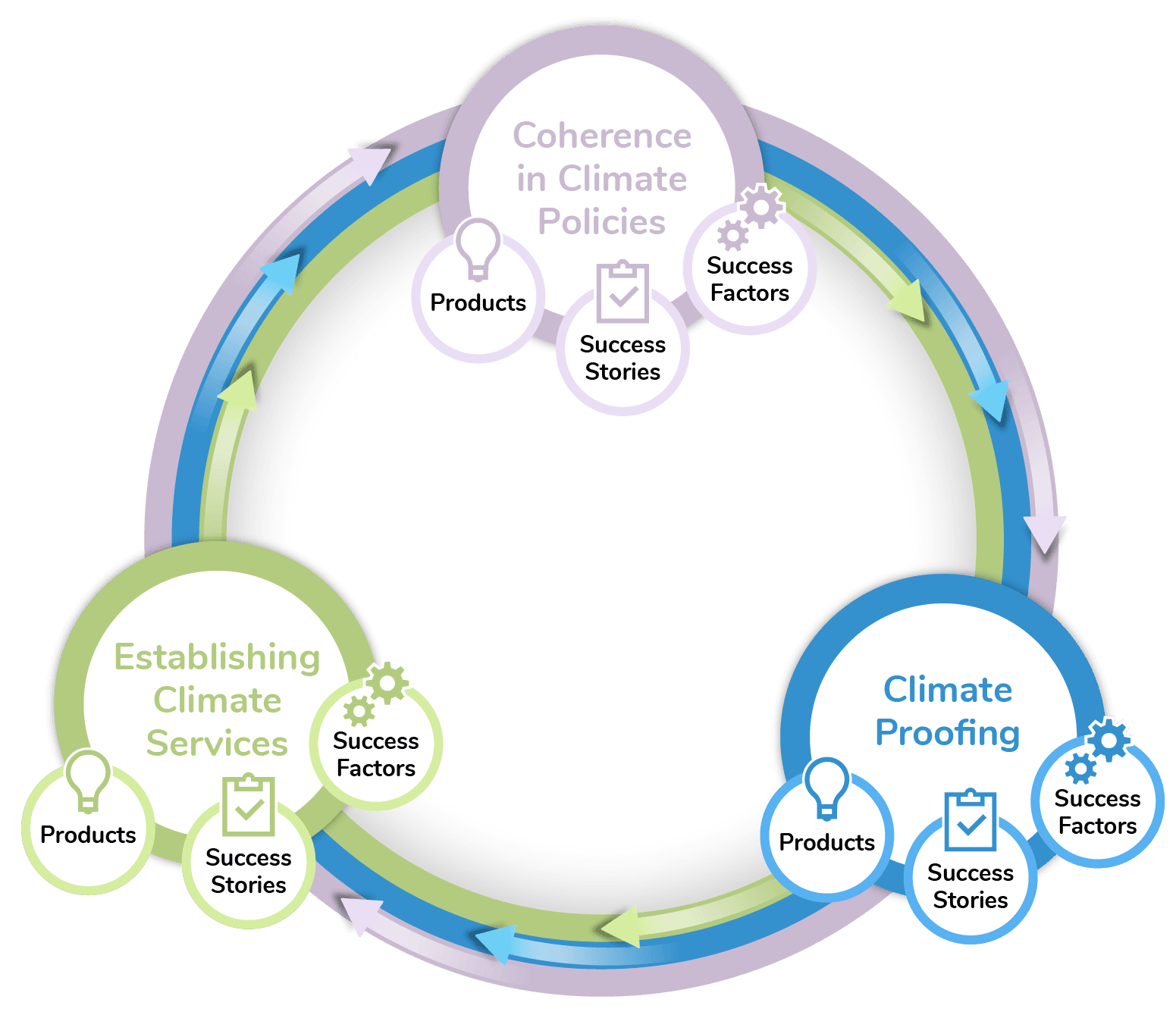

Coherence in Climate Policies – Products

Coherence in Climate Policies

- The challenge of aligning climate change adaptation policies with infrastructure-related policies is a problem faced by many countries. In addition, there is a need for closer coordination between different actors to ensure policy coherence.

- While the National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHS) play a core role in enhancing Climate Services, their lack of political clout makes it difficult for them to influence national policies and budget allocations.

- To address this, Climate Services need to become part of the agendas of both climate and infrastructure policy.

Coherence in Climate Policies – Success Stories

Coherence in Climate Policies – Success Factors

- Creating policy coherence requires both horizontal and vertical policy coherence, which means that infrastructure resilience needs to become part of adaptation plans and climate change adaptation needs to be integrated into the infrastructure planning and investment cycle across all government levels.

- New alliances and bargaining arenas for negotiating the process of bringing infrastructure and climate policy together are also needed.

- Identifying an appropriate action track around which an adaptation coalition can be formed is key to achieving policy coherence.

- Change agents, including rule setters, sectoral champions, and potential multipliers, can play a vital role in driving this process. Incorporating all relevant actors along the value chain into such networks is necessary.

Risk Management and Climate Proofing

Although there is agreement that infrastructure must become more resilient to climate change, action to incorporate climate change into infrastructure planning and management is lacking.

- This is due to various reasons, such as the perception that there are more pressing issues, challenges in obtaining and using climate services, and a lack of regulatory incentives. These challenges make planning infrastructure to last up to 100 years particularly difficult. Decision-makers are only willing to invest in adaptation if there is a solid regulatory foundation in place.

- This becomes especially apparent when considering Ecosystem Based Adaptation options. For example, if mangroves are rehabilitated in addition to building a dyke, this does not only provide added protection from flooding that would otherwise need to be dearly bought via an even higher dyke, it also provides a habitat to local fauna, reduces sediment loss and can serve as carbon sink.

- The realisation that climate proofing is necessary is not new. Many have set themselves upon developing tools for the climate-proofing of infrastructure. This plethora of tools and approaches, though potentially overwhelming, also provides infrastructure planners with a treasure chest full of tools to mix and match based on their needs.

- Likewise, Climate Services providers are seldom systematically incorporated into climate proofing processes, making it hard for them to know and deliver upon what is needed from them.

- There is therefore a need to provide guidance both on how to tailor approaches to different decision-making contexts and on how to develop and use the Climate Services that go along with this.

Climate Proofing – Products

Climate Proofing – Success Stories

- Vietnam: Infrastructure practitioners unite to reduce climate risks

- Brasil: Climate-resilient infrastructure in Brazil

- Costa Rica & Vietnam: How to make infrastructure more resilient towards climate change

- Costa Rica’s transport infrastructure to be made climate proof

- Climate risks in Africa’s Nile region – new climate proofing concepts for the Greater Nile Region

Climate Proofing – Success Factors

- Climate Proofing and Risk Assessment measures are expensive. Prioritization is therefore important.

- Involve a diverse set of actors, ranging from climate science to infrastructure operators to infrastructure service receivers.

- Under normal conditions a climate risk assessment should last no more than 8 to 9 months

- If the climate risk assessment is conducted for the stage of feasibility rather than for the stage of after construction, the cost are much lower for the former than the latter, pointing out the economic benefits of early investment.

Establishing Climate Services

Climate information is crucial for effective adaptation, particularly in the infrastructure sector, where structures are built to last for decades.

- However, the information needed for infrastructure planning is different from that used in agriculture, and currently, there is a lack of tailored climate information for infrastructure planners.

- The challenge is to develop climate services that meet the specific needs of infrastructure planners, considering the different decision-making contexts and vulnerabilities of each component.

- In order to address this challenge, taking a holistic view that involves all actors along the value chain from climate data to adaptation decisions is important.

- Often, one of the main challenges is the lack of an institutional or governance framework that allows for continuous cooperation among providers and users of climate services.

- Although National Meteorological and Hydrological Services are important stakeholders in the provision of climate services, they cannot take the lead in their development without additional resources and extensive capacity development.

- Therefore, a more inclusive approach involving all actors along the value chain is needed.

Establishing Climate Services – Products

Establishing Climate Services – Success Stories

Establishing Climate Services – Success Factors

- Take an inclusive approach to the development of climate services, involving all actors along the climate services value chain.